As a Strength & Conditioning coach I love this time of year. Schools are getting out so athletes have more time to train, watch what they eat, and get a decent amount of sleep. Fall sport athletes are beginning to ramp up their training. Spring sport athletes are coming off their season and are motivated to get back into the gym to make the next season even better. High school seniors are excited about playing in college the next year. Our college athletes return home and it’s genuinely exciting to hear them talk about their year. Lots of positive energy.

Unfortunately, some of our excitement about summer diminishes when we get the inevitable questions about summer training packets. For those that aren’t familiar with this, the idea is that college coaches want their athletes to work out over the summer instead eating Doritos and playing Fortnite. While this is generally a good idea, the execution of that idea is often full of problems and everybody suffers because of it. In most cases I think it’s a lack of communication or knowledge, and that if the information was out there and discussed it wouldn’t be as big of an issue.

I’ve had this conversation so many times over the past month that I thought I would put something in writing so in the future I can just direct them to it, maybe have them share it with their parents or ask their coach to read it. I’ve seen too many good athletes move to suboptimal summer training programs.

Here’s how a typical conversation goes:

Athlete: I got my summer packet full of workouts that my coach sent me. It doesn’t look anything like what we’ve been doing. My coach wants me to do their workouts. I’m not sure what to do next.

Me: How about you show me your workouts and we’ll talk about it.

*Athlete shows program with lots of single-leg stuff, dumbbell work, and “core” exercises. Maybe some cleans from the hang and back/front squats, but not really programmed for strength.

Me: So you see a lot of goofy stuff in summer packets for a couple reasons.

First, the S&C coach there doesn’t know what equipment you have access to. Most high school athletes only have access to a Gold’s or a Planet Fitness. And if they did have access to a squat rack, prowler, bumper plates, lifting platforms, etc., the chances of them knowing how to properly squat, clean, press, or anything else we do without hurting themselves is usually not great. So a majority of the exercises on here are things you can do in your parents’ basement or a typical gym. They simply have to write a summer program that most people can actually do.

Second, the S&C coach doesn’t always have control over what goes into the S&C program. This sounds backwards, but a lot of times sport coaches mandate things either due to their ego or because ” I did it this way, and so will you”. This is why you see softball and baseball players entering college having to do a timed mile as their conditioning test. Or why you see volleyball players who are not allowed to lift anything overhead. The coach demands something ridiculous, and if the S&C coach doesn’t follow through, they are viewed as “not a team player” and are possibly out of a job.

A third reason sounds a little harsh but the reality is that you just might not have a good S&C coach in charge of your team. We occasionally send a kid away to a college program only to have them return in the spring weaker and less explosive, and it wasn’t for a lack of participation on their part. A big D1 school might have over 10 S&C coaches on staff, plus graduate assistants. Some of them are really good, some are there because they knew the right people, and some are still in school as GA’s and are literally still learning the basics. This is why you can look at some schools and see a vastly different quality of training programs between sports. A smaller school like a D2 or D3 program, if they are lucky, will have 1-2 S&C coaches in charge of training all sports. They may or may not have decent equipment and support from the coaching staff. And if the sport coach is the one in charge of summer training, they usually put together a program based off what they did while they were playing the sport, which only perpetuates the problem.

It is at this point that the athlete has a bittersweet epiphany. They understand that they need to train to be in the best shape possible heading into their collegiate athletics career, but they also feel pressured into following the workouts they are given to make their coach happy and make a good impression. It’s a difficult situation to be in, and most people will panic and blindly follow whatever they were given by their coach. I am obviously a little biased, but I believe that an athlete should do whatever will best prepare them for the next level of competition. There can be a big difference between a summer of good training vs. a summer of poor training. In the end it is up to the athlete to decide what is best for them.

To best explain all this, I’ve collected some summer programs from our athletes to show you examples of what I’m talking about.

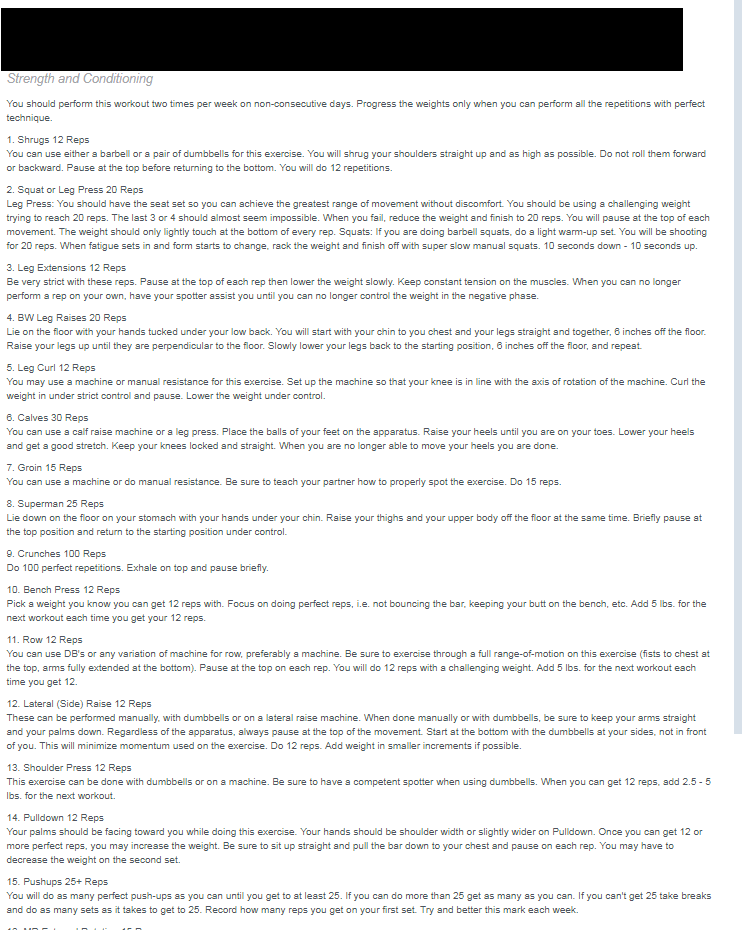

The above program is from the S&C dept at a major D1 school and is a pretty good example of the first point that I explained to the athlete above. Most schools do not know what you have access to, so they make an assumption that you are at a normal gym that doesn’t have power racks, bumper plates, and good conditioning equipment. In this case, they are trying to get you to do anything, so that you’re not completely deconditioned when you arrive in the fall. While this is probably better than doing nothing at all, any athlete who has been participating in a good training program that includes cleans, squats, pulls, presses, snatches, and effective sprint/conditioning work will take a major step back on a program that does nothing but machine-based or dumbbell training for high reps.

If you have access to a legitimate S&C program that gets you moving correctly and gets you stronger and more powerful, the difference between doing that and what’s pictured would absolutely be night and day.

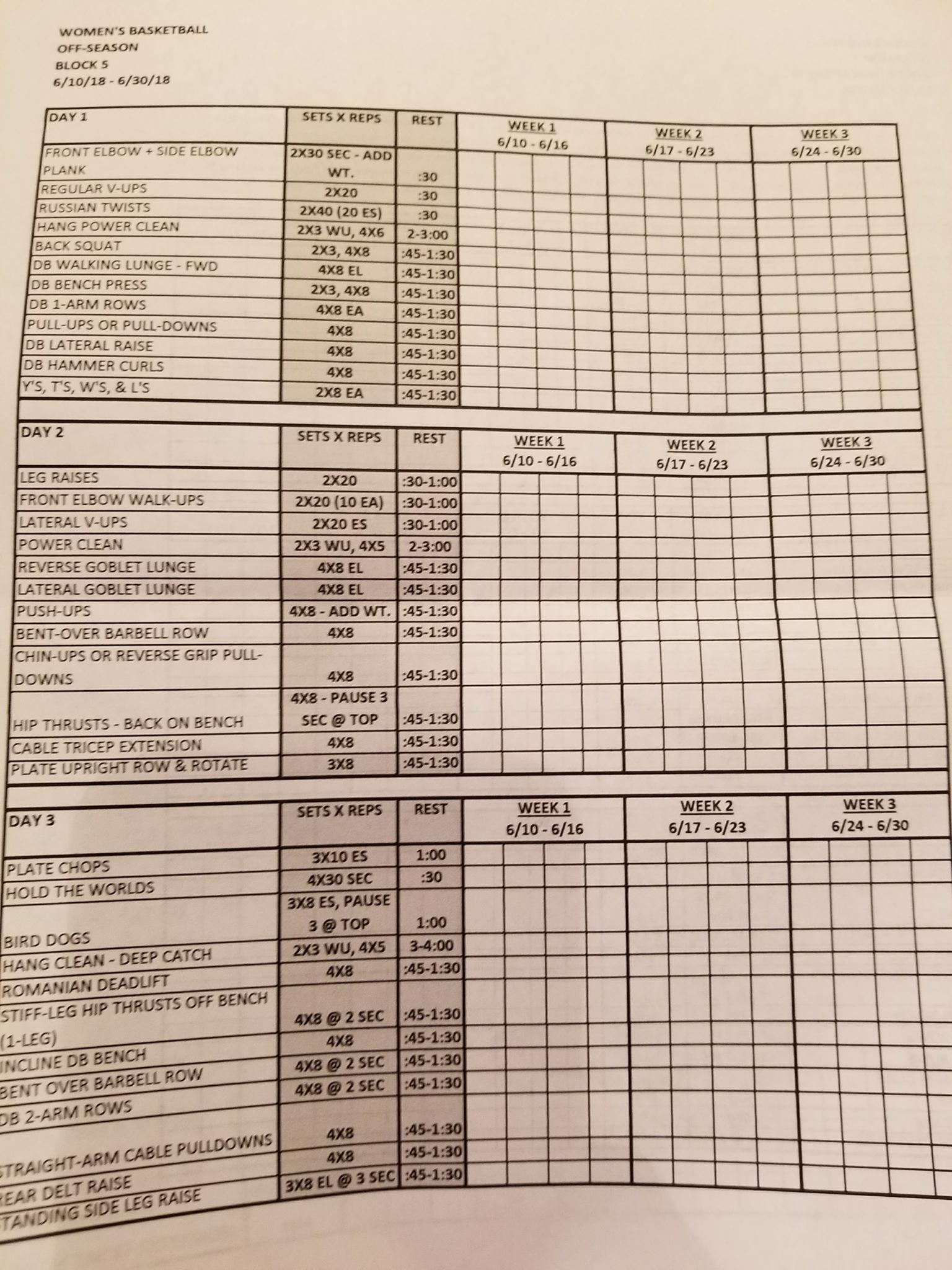

Below is from the summer packet of one of our female basketball players who is heading off to a high-level D2 program. This is a high school girl who squats well over 200 for reps, cleans over 135, and moves around really well on the court. While they include some squats and cleans (although for higher reps), most of the training program of lunges and dumbbell work takes away from time and energy that could otherwise actually be spent developing athletic qualities. And because our athlete already has a decent training base from squatting, pressing, and pulling heavy, she actually de-trains and becomes a worse athlete on this program because it’s not stressful enough relative to where she’s at.

That’s actually an important topic to discuss further because in the end we want to be able to give the athlete a program that will get them in the best shape while making the most efficient use of their time. There has been a push by some organizations recently to include “functional training” – lots of single-limb isolation, core work, and rehab/prehab exercises. This is a colossal waste of time that could otherwise be spent doing the things that actually make you a better athlete. A well-designed program can cover the entire body in 3-5 intelligently selected and progressed exercises each day. It does not need to include a bunch of assistance exercises because the program has been intelligently laid out to already have those things covered. Anything further than that is simply making things complicated for the sake of looking fancy. Lots of people will do this in order to make a name for themselves, so it is unfortunately up to the athlete to see through the bullshit and make a decision on the best way to train.

Another important distinction to make here is the difference between developing athletic traits and displaying them. This could be an entire article by itself (it will be put on the list!) but there are many things you see that look fast and explosive but do nothing besides display an athlete’s already-present athleticism. Want to actually run faster, cut harder, and change direction quicker? Take your 95lb squat and double or triple it. Easily doable in a couple months if your S&C coach knows what they’re doing. In athletics your muscular system serves as your engine, suspension, and brakes. You can play around with cones and ladders all you want, but you won’t get a whole lot better because your limiting factor is leg strength.

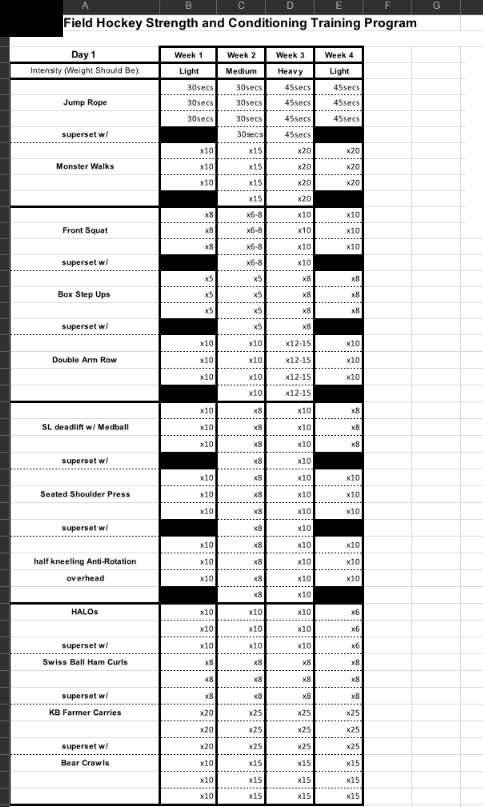

Above are from summer workout packets that some of our athletes received from their colleges for their upcoming soccer and field hockey seasons. Do you understand that none of these exercises are going to make the athlete either stronger or better conditioned? Clean & Jerks and deadlifts done with a med ball? Ab exercises for 200 reps? There is a trend here. Lots of endurance/bodybuilding exercise and nothing really that hard. This type of program doesn’t really do much for an athlete besides expose them to the idea of working out.

So all this explanation doesn’t really help much if I don’t describe what athletes need to be doing, right?

For starters, they need to have developed a base level of Strength. If you are a female athlete and you cannot squat a 185# bar to depth, or a male athlete who cannot squat 315, you are woefully unprepared for the rigors of the next level. The single biggest difference you can make from both a performance improvement and injury prevention standpoint would be to spend some time under a bar getting stronger. We have written on this pretty extensively in previous articles, but I’ll link to one HERE that will give you a pretty good explanation as to why you need to train for strength. Depending on what your sport is and how much time you have to train before you leave for school, we start to look at the other athletic qualities you need to develop.

Here’s what most good, well-equipped S&C programs will have you doing:

- 2-3 days of squatting. With a barbell for sets of 2-6 reps. Dumbbell squats, goblet squats, split squats, or nearly any other squat variant does not provide enough systemic stress to produce a meaningful increase in strength compared to a barbell back squat.

- 2-3 days of pressing. This might be overhead or a bench press. Once again, with a barbell.

- 2-3 days of pulling. Deadlifts are the best, but RDLs are also common in S&C programs and aren’t the worst thing you can do. This also includes chins, pullups, rows, etc.

- 2-4 days of the Olympic lifts. The Olympic lifts (clean, snatch, jerk, and their variants) are arguably the best way to develop rate of force production (read: explosive power, like the kind that makes you run faster, jump higher, and hit things harder) as you get stronger. Their frequency and loading will depend partly on how proficient you are at them, how good your S&C coach is at teaching them, and partly on your total training volume.

- 2-5 days of conditioning. This would include sprinting/jumping work depending on the sport. It is important to understand that your conditioning must match what you’re trying to prepare for. Most sports involve brief periods of high-intensity effort followed by a rest/lower activity period. You should condition in a way that adequately trains those energy systems (<–Please read if you don’t know the difference between energy systems). A 1 or 2 mile run will not prepare you for most sports.

- Sports skill work most other days. This should be obvious, but many people miss the forest for the trees here. If you want to get better at basketball, you need to practice your basketball skills. The same applies to any other sport. Getting stronger and in better shape will make you an all-around better athlete, but there is still a large skill component to athletics. This must be practiced and cannot be emulated in the weight room.

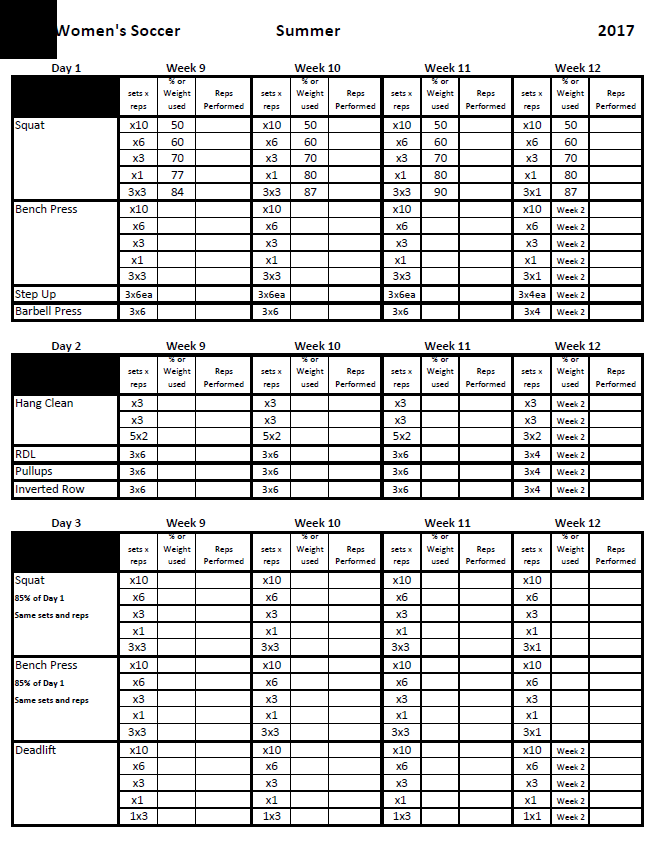

Here’s an example of a decent program that one of my athletes sent me. This came with a couple days per week of smart sprint work and provides an all-around strength and conditioning program that doesn’t waste anyone’s time. Not exactly how I would program things, but it’s 100 times better than most of the summer workouts I see.

Now that all the information is out there, hopefully you have a better idea of why you see some of the things you see in these workouts. Ask your coach or school questions, try to figure out if they have a reason for why they do things a certain way. In many cases if you take the time to explain “this is what I’m doing, these are my goals, it’s all under the supervision of someone who works with a lot of athletes”, the school is honestly just happy that you’re willing to put in the work.

Tags: Athlete, College Sports, Conditioning, offseason, Strength